Swimming & Style

WRITTEN BY LIZ FARIAS

COVER PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE SUBVERSIVE SIRENS

Guest-curated by British fashion historian, Amber Butchart, Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style was exhibited at the Design Museum in London from March 28, 2025, through August 17, 2025. Visually eclectic and educational, the exhibition dives into everything from the origins of community pools and the evolution of swimsuit fabrics to swimming as a social class indicator. There was even a mermaid section! It’s one of those rare exhibitions where you end up taking fifty photos of the excerpts and actually go back to read them later. I spent a good chunk of time there and still felt rushed, which is always a sign of a well-curated show.

What struck me most was how cohesive the storytelling felt despite the exhibition’s breadth. It flows seamlessly from the invention of public pools to the rise of lidos to the resurgence of natural swimming spaces, and it manages to balance dense historical context with pure visual intrigue. Even without reading the blurbs, the design and layout are captivating. And when you do stop to read them, you walk away amazed by details you’d never considered before.

David Hockney’s Swimmer (1982)

One of my favorite exhibits was David Hockney’s Swimmer (1982), created for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Hockney’s pool paintings are closely associated with 1960s California, when private backyard pools became symbols of affluence. I’ve always loved triptychs for the way they play with scale and perspective, and Hockney uses that format beautifully here. Across three panels, he fragments and reassembles the poolside view, creating shifting vantage points that mirror the distortion of water itself. Hockney has long used multi-panel compositions and photographic drawings to challenge traditional ideas of perspective, offering instead a kind of panoramic intimacy, a scene you can’t take in all at once but have to experience piece by piece.

PHOTO: PHILLIPS.COM

The work is both playful and reflective: a celebration of California’s sun-drenched leisure culture and a nod to Hockney’s own obsession with swimming pools, right down to the patterned floor inspired by his own backyard. The piece was part of a broader visual culture surrounding the 1984 Olympics, which commissioned 15 official posters by well-known artists, including Hockney, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein. The posters reflected Los Angeles’s emphasis on positioning itself as both an athletic and cultural hub during the Games.

How A Swimsuit Gets Made

I’d never really questioned why every swimsuit I’ve owned is made from some mix of nylon and Lycra. It’s always been the default. The exhibit made me realize that wasn’t always the case and that the fabrics we wear reflect decades of technological innovation and marketing decisions.

In the 1920s, swimsuits were often made of wool, part of a “hygienic clothing” movement that claimed animal fibers were better for the skin. By the 1930s, Lastex, a rubber-core yarn, made swimsuits more form-fitting and flexible, reshaping both their look and function. Then, in 1939, DuPont introduced nylon, one of the first fully synthetic fibers. Marketed as modern, fast-drying, and easy to care for, it became the foundation for the nylon-elastane blends that dominate swimwear today. These fabrics hold their shape, dry quickly, and last far longer than wool ever did.

The tradeoffs are that synthetics don’t breathe as well, shed microplastics, and are hard to recycle. Two summers ago, I bought a crochet bikini and hesitated to wear it while swimming. Having grown up assuming all swimwear is built to perform, holding something delicate and unconventional made me think about how much technology shapes our expectations. Today, most mass-produced swimsuits still rely on nylon-elastane blends, though newer materials like ECONYL — regenerated nylon made from discarded fishing nets — hint at a more sustainable future. Seeing this timeline made it clear that what feels standard today is the product of decades of innovation and trends, not an inevitable choice.

Another exhibit also highlighted performance-driven swimwear, like the Speedo LZR Racer from 2008. Developed with NASA scientists and designed for Team USA by Comme des Garçons, the low-friction, welded seams, and compression panels streamlined the body. At the Beijing Olympics, 94% of gold medalists wore the suit, but it was so effective that it was banned in 2010 for “technical doping.” It’s striking to see how far fabric innovation has come, from heavy wool suits in the 1920s to a point where clothing can influence Olympic outcomes.

Swimsuits as Play

While much of the exhibition focused on innovation and utility, it also celebrated the joy and spectacle of swim culture. As someone with Brazilian roots, I’ve always known how bold and trend-forward Brazilian swimwear can be. There’s a style for every taste: the barely-there fio dental (“dental floss”) bikinis perfect for minimal tan lines, bold maximalist patterns that feel like wearable art, and everything in between. What ties it all together is a kind of unapologetic vibrancy — an embrace of the body, the beach, and life itself. That spirit came through in Fernando Cozendey’s gender-neutral Lycra jumpsuit, designed to move from Carnival to the club. His work was on display at both Rio’s Carnival and the 2016 Olympics opening ceremony, embodying Brazil’s playful relationship with swimwear as performance and self-expression.

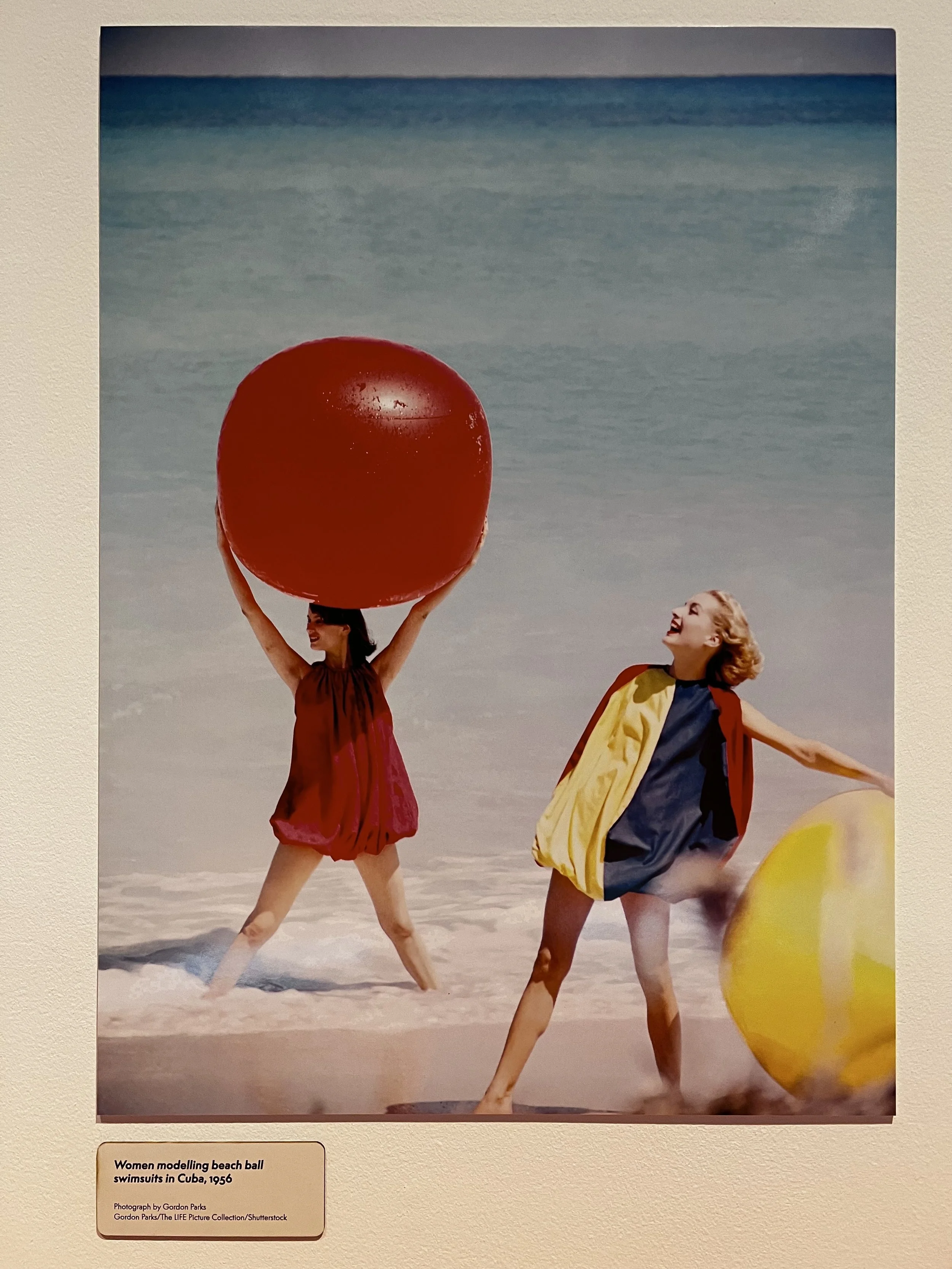

I also loved Gordon Parks’s 1956 photograph of women modeling inflatable beach ball swimsuits in Cuba. It’s surreal, joyful, and deeply stylish. I love how this image plays with scale. Together, these pieces highlight swimwear’s role beyond practicality, revealing how it shapes culture and celebration.

Swimsuits as Activism

I loved that the exhibition included swimwear as a form of activism. Designed to spark conversations around menstruation and period stigma, Hannah Whelan’s Blob Swimsuit stood out. It transforms something functional into a statement while blending humor, creativity, and politics. Similarly, the Swimming in Plastic campaign by Surfers Against Sewage had the Jubilee Pool in Penzance filled with plastic bottles to highlight ocean pollution and corporate responsibility. Both projects show how water can become a canvas for activism when addressing oppression, environmental crises, and societal taboos. I appreciated how the exhibits treated these works not as novelty, but as meaningful interventions that make social and environmental issues visible in a playful yet urgent way.

Mermaids

This section felt like a candy store for someone obsessed with mermaids and water folklore. As a fantasy lover who grew up with The Tail of Emily Windsnap books and merfolk in TV and film, it made my heart flutter. I loved seeing the modern mermaiding community highlighted, where people swim or perform as mermaids professionally or as a hobby. Realistic tails, sculpted by Silvo Đorđević (aka Siki Red), are incredible works of art made from clay and silicone, blending craft and imagination. Trust, one day I will have the money to commission my own tail!

I also appreciated the exhibition’s attention to representation and cultural context. Halle Bailey’s portrayal of Ariel in the 2023 live-action Little Mermaid sparked the Mermaidcore trend and, despite the backlash she faced for not being white, the exhibit highlighted the care taken in her underwater training, including how her locs move in water. As she said, “As a Black woman, hair is spiritual… I feel like that’s what mermaid hair would be anyway.” Seeing this celebrated in the exhibition felt powerful, serving as a reminder that spaces of fantasy and imagination can, and should, reflect diversity. For Black girls, seeing magic in a mermaid who looks like them is an affirmation that everyone deserves to feel magical.

Swimming & Identity

Lastly, this exhibition examines various cultures and shows how identity is deeply woven into swim culture. I loved how it tackled colorism with suntanning — dark skin was historically read as a marker of being higher class, but only if you were already light. That double standard, tied to leisure and tourism versus outdoor labor, still persists today. It also highlighted historic mistakes, like swim caps being banned for Black swimmers, and stark disparities in who has access to pools. I think it’s so important for exhibitions to point these things out, not just to educate, but to show how the pain of past policies continues to ripple through the present.

ARTWORK: PHOEBE BOSWELL

The Saltwater Within Us, The Depths of Our Grief, The Leagues of Our Love, 2023

Water itself felt like a recurring touchpoint. It carries collective trauma — for enslaved peoples, for marginalized communities excluded from pools — but it’s also a space being reclaimed. Alice Dearing and the Black Swimming Association, The Subversive Sirens, and Phoebe Boswell are all examples of how people are transforming water into sites of empowerment and healing. Yusra Mardini’s story was another moment that struck me: fleeing the Syrian civil war, she swam for her life and saved others, later competing on the Refugee Olympic Team. Her story reminds me that oceans are also critical access points in contemporary crises, war, and migration.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, it’s intriguing to think about how water is designed, regulated, and navigated in ways that reflect political, social, and historical forces. Some of my friends have fears of water, and seeing this exhibition made me reflect on how access and identity shape our relationship to something as seemingly natural as a pool or the ocean. Water is not neutral. It carries memory, and the meaning of these spaces is ever-changing. Whether you’ve grown up on the water or never learned to swim, your relationship with it can speak volumes about your place in a larger context.

SOURCES:

Design Museum. (2025). Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style. Design Museum. https://designmuseum.org/exhibitions/splash-a-century-of-swimming-and-style

Phaidon Editors. (2014, September 18). Remembering the LA Olympics. In The Phaidon archive of graphic design. Phaidon. https://staging2.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2014/september/18/remembering-the-la-olympics/